Extraordinary people, remarkable stories

B.R. O’Hagan has one of the most fabled client lists in the world of ghost-writing. Across two decades he has written books and articles for some of the most influential and interesting people in America. From a top diplomat whose love of the Old West defined his character and his career, to an industrialist whose passion for Italian sports cars inspired him to create one of the world’s greatest vintage racing car collections, O’Hagan’s books are a who’s-who of business, politics and the tech world.

To help capture the essential spirit of his subjects, O’Hagan crafted a fictional prologue for each of their books that speaks to their deepest passions. For one subject it was baseball, for another it was the history of the exploration of the American West in the early 19th century. Pioneer aviation inspired the head of one of the largest aircraft manufacturing firms in the world, while magic–especially with playing cards–has been the lifelong pursuit of the CEO of a global energy company.

The inspiration for compiling this small book came in part from the underlying premise behind O’Hagan’s novel, Martin’s Way: “No one lives an ordinary life.”

Each of us has a story to tell, and every one of those stories deserves its own special prologue. It is the author’s hope that you, too, will tell your story and craft your prologue to share with your family today, and for generations to come. Please enjoy the excerpt from one of the prologues, below.

“Great storytelling!”

The Explorer

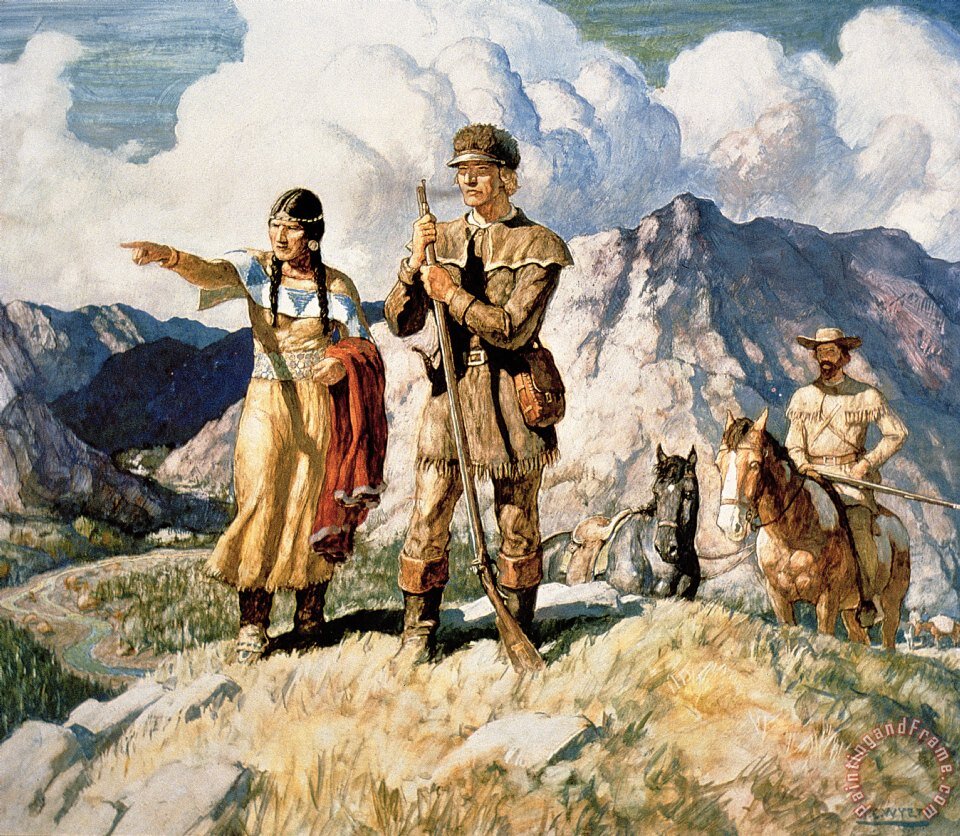

This prologue opens a book about the founder and CEO of one of the world’s largest privately-held construction and engineering companies. He has been fascinated all his life by stories about the fur trappers, mountain men and surveyors who braved the vast expanses of the American West in the early days of the 19th century. Here is an excerpt:

April 1826 -Missouri Territory

The explorer shifted in his saddle and checked to see that his Hawken rifle was secure in its leather sheath. From his vantage point on the limestone ridge, he could see for miles along the meandering Platte River, brown and silty from hundreds of creeks that tumbled into it during the late spring rains. The shallow, swampy waterway was lined with cottonwood trees in full bloom and dotted with small islands. It was a pretty vista in the gathering twilight, but the explorer knew the braided riverbank below him would soon be swarming with thick masses of ravenous mosquitos. As for the Arapaho encampment he had spotted a few hundred yards from the bank, well, the more leeway he gave them, the better. His history with the Arapaho and their neighboring tribe, the Utes, hadn’t always been so friendly.

His journey had begun three months earlier at the headwaters of the Platte high up in the Medicine Bow Mountains of Colorado, a region teeming with antelope, deer, and buffalo. The spring thaw opened the high country trails almost overnight and made for easy travel from his campsite on Grizzly Creek toward his final destination at the confluence of the Platte and Missouri rivers. In all, he would be traveling alone on horseback through mostly unpopulated areas for more than nine hundred miles. He’d hunt for his own food, repair his own gear, and also deal with any medical emergencies he might face.

The purpose of his journey could be found in the watertight pouches strapped to the side of his pack horse beside his other supplies. Inside the pouches were eight leather-bound journals, each containing about a hundred sheets of parchment paper. The pages of three of the journals were filled with his notes including drawings of plants, animals, and landscapes, observations about the weather, locations of native encampments, estimates of the size of buffalo herds and the quantity of beaver lodges, and measurements of the depth of the river and its tributaries.

The explorer was not a scientist or a geographer. In fact, until a year ago he had been a beaver trapper. His family moved from Ohio to St. Louis (population nine hundred) in 1796, where he was born on April 30, 1803, the very day that the Louisiana Purchase Treaty was signed in Paris, France. The significance of his birthdate was not lost on the explorer: With the stroke of a pen and a payment of only $15 million, the United States was suddenly in possession of an additional 828,000 square miles of territory. It was, without question, one of the most important and transformative land transactions in history. The explorer would grow up to become a part of the vanguard of frontiersmen who would follow in the footsteps of Captain Meriwether Lewis and Lieutenant William Clark’s monumental 1804–1806 Corps of Discovery expedition.

On his 17th birthday, the explorer set out from St. Charles, Missouri, the same small town from which Lewis and Clark had begun their epic journey sixteen years earlier. The Corps of Discovery had been charged by President Thomas Jefferson with the task of exploring and mapping the new territories, finding practical travel routes to the West, and “planting the American flag” in the far-flung regions as a way of keeping European nations from attempting to take control of any of the new lands.

His own journey of discovery would take the explorer to places even Lewis and Clark had not seen. He learned how to trap beaver, prepare their pelts and take them by canoe to market. He traveled back and forth across the endless expanse of tall grass prairie in search of untapped streams teeming with beaver lodges. He dressed like an Indian from his thick moccasins and elkskin trousers to his buffalo-hide belt and fringed jacket dotted with porcupine quills. He lived under the open sky when the prairie temperature was sweltering, and when the great blizzards blew down from Canada to blanket the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains under sheets of ice and snow, he hunkered down in a log lean-to. He fought off packs of hungry wolves at night and rattlesnakes in the heat of day. Once he sat atop a sandstone ridge and waited for two full days as a steady stream of buffalo thundered past him. He estimated there were more than 250,000 animals in the herd.

He went for months at a time with no human companionship and the few people with whom he visited were more likely to be Pawnee or Cheyenne or Dakota than trappers like himself. A year earlier he attended the first rendezvous of traders and fur trappers in McKinnon, Wyoming. Almost a thousand people were in attendance, and after a week of trading, resupplying, catching up on news of the world and eating and drinking more than he had in years, the explorer was ready to return to the life of solitude and danger he loved so much.

His plans changed, however, during a chance meeting with a trader from St. Louis. The man was part of a commercial syndicate made up of businessmen who believed that the unlimited potential of the vast western territories was not only untapped, but in fact, the size and scope and potential of what all that land represented was barely understood.

“The truth is, we don’t have any clear idea just how many opportunities are out there,” said the trader as they shared coffee and bacon one morning. “We just know there is no limit to what can be accomplished if we are willing to take the time to study and explore every inch of these lands and match the opportunities waiting out there with the needs of all those folks in the East.”

The American population is exploding, explained the trader. And with limited jobs, higher land prices, and greater competition for resources, pretty much the whole darned nation was getting ready to head out West, in his estimation.

“There is going to be a great migration,” said the trader. “The biggest in history. And not just from here in America but from all over the world. It may not happen next year or the year after that, but it’s coming; nothing can stop it. Folks will travel across the prairies in wagons, they’ll navigate the rivers on barges, they’ll ride horseback; heck, they will walk if they have to. Whole families, thousands and thousands of them.”

“And when they get out here,” asked the explorer, “what will they do?”

“That’s the question, isn’t it,” replied the trader. “Sure, they will farm and ranch and some will settle in new towns and open shops and businesses. But there will be more, much more. Shoot, son, the settlers headed this way are going to need everything, from saw mills and blacksmith shops to dry goods stores, schools, churches, and everything in between.”

“So that’s what you are going to do, build towns and such,” said the explorer.

The trader chuckled. “Look out there,” he said as he swept his arm in the direction of the mountains to the west of the meadow in which the rendezvous was encamped. “Row upon row of peaks marching north and south with all that green forest on the slopes and that glorious snow on the caps. Some of them are over 14,000 feet high, and darned if you can’t see them for over a hundred miles out into the prairie. You probably see those mountains as obstacles, something that prevents you from getting where you need to be.”

The explorer nodded. The great granite peaks had their beauty, no doubt about it, but for someone in his business what they really represented was toil and danger, pretty much in that order.

“But that’s not what they are, son. They are signposts for travelers, ones that cannot be missed or ignored. And they are probably packed with gold and silver, not to mention covered with the lumber that we’ll need to build those homes and towns. Someday, and don’t think me crazy, but someday I am convinced there will even be roads through those mountain passes that people will be able to travel year-round.”

Now it was the explorer’s turn to chuckle. “That would be something,” he said politely. “It would sure make my life a whole lot easier. But I don’t expect you’ll be building them roads this year.”

He stood up from the camp chair and made ready to leave. That’s when the trader made the explorer the offer that would change his life forever.

“No, my syndicate won’t be building roads through the mountains this year. First we need to find out more about those mountains, the rivers they spawn, and the best way, frankly, for folks to get from Point A to Point B the best, fastest, and most economical way possible. Let me show you something. . . .”

The trader unfurled a large map and laid it on the log table by his tent. It was a representation of what was known about the lands included in the Louisiana Purchase starting at the Canadian border on the north, then south to New Orleans, and from St. Louis in the east to the high deserts of western Colorado. Other than a few small settlements, the tracks of major rivers, and the lines denoting the trails blazed by Lewis and Clark and a generation of trappers, the map was mostly empty. Tens of thousands of square miles were simply blank spots on the oilcloth map.

“This is 1825,” said the trader, “and it has been nearly 20 years since the Corps of Discovery’s explorations of the West. Here we are today, and we still haven’t filled in the blanks on our maps. My partners and I are going to change that. And you are going to help us.”

That last sentence got the explorer’s attention. What did he have to do with such business? He didn’t know a thing about mapmaking or have any of the scientific knowledge needed to identify, gather, and preserve plant and animal specimens. Oh, he could get from Point A to Point B, all right. He knew how to read the stars, how to use the transit of the sun at midday to fix his position, even how to use distant rocks or other landscape features to plan his course and stay on track. And if any of those navigational skills failed him, he just relied on his gut instinct. He had never been lost, not even in the boundless sea of grass that was the American prairie.

“I appreciate your confidence in my skills,” said the explorer. “But I am a fur trapper, not a cartographer or a botanist. I think you’re talking to the wrong fella.”

“And I’m sure I am talking to exactly the right man,” said the trader. “Do you know the Platte River?”

“I do,” replied the explorer. “I’ve travelled along much of it these past several years. Used to be some prime beaver trapping in the north, but there aren’t near as many as there used to be.”

The trader smiled. “That’s just the kind of observation we want our explorers to make. And not just the observation, but some of the facts behind it. How much has the beaver population declined? Why? Are they being overtrapped, or is there some kind of disease responsible? Does the decline look like it’s temporary, or is it here to stay?”

“And that kind of information is valuable to you?” asked the explorer.

The trader finished his coffee and set the cup on a rock near the fire. “I’ll tell you something,” he said. “That kind of information is more valuable than every stack of beaver pelts being traded at this rendezvous. And since I’m one of the folks putting out his hard-earned dollars for those pelts, you can trust that I know what I’m talking about.”

“So you want me to do a survey of beaver populations?”

“Not exactly. I want you to come with me to St. Louis to meet my partners. Then I want you to spend about a month learning from our experts. And when you’ve done that, I want you to spend the next year or so traveling from the headwaters of the Platte to its confluence with the Missouri River.”

“Gathering all them facts? But if you already have folks in St. Louis who can do the work, why not send them,” asked the explorer.

“That’s simple,” replied the trader. “Not one of them could get from Point A to Point B the way that you can. Especially out here.” (end of excerpt)